At first, I wasn't sure why Valley of the Dolls wasn't included in chick lit week for my literature course. After all, it has a pink cover, follows three young women through various career arcs and romances, and has enough sex to qualify. Plenty of handsome men and beautiful girls to go around.

But from the first chapter, I knew that Valley was in a category apart for certain. Though Anne, the main character in the first part of the book, is beautiful and pursued by a millionaire, Jacqueline Susann sets a tone in the beginning that makes the reader feel as though Anne's life is much more real than any chick lit protagonist could ever hope to be. Though a millionaire wants to marry her, she lives in a singularly squalid one-room apartment; and though her boyfriend seems to be a sweet, unremarkable young man, it is soon revealed that he is, in fact, connected with a lotof money gained through very dubious means.

We discussed chick lit a lot in our course, at least during the class assigned to it, and we came to the conclusion that though they are regarded as 'fluff,' they do deal with important issues such as body image, female self-worth, shopping addiction, and the angst inherent in being a single 30-something in London. Still, a lot of us were left with a vague sense of contempt for the genre, though we were unable to articulate it when the professor asked, 'How can you call this fluff if it deals with these issues?'

But Valley of the Dolls answers his question clearly. I could never call Valley 'fluff'; though it was popular, and therefore it has the stigma of common approval, it is also a complex, raw examination of show business, women, relationhips, and what people will do to protect what they think is valuable.

But Valley of the Dolls answers his question clearly. I could never call Valley 'fluff'; though it was popular, and therefore it has the stigma of common approval, it is also a complex, raw examination of show business, women, relationhips, and what people will do to protect what they think is valuable.Valley deals with addiction (mainly to pills, called 'dolls'). It deals with body image (all three of the characters make livings off of their bodies). It deals with being single, or rather not being able to get who you want, until you finally get them and realize it's not enough. It deals with the horror of having to take six Seconal and still not being able to sleep; it addresses cancer, insanity, fame, fortune, love and adultery.

And it does it all at the same time.

Chick lit can only deal with one issue per book, sometimes per series. Jemima J is about body image. Full stop. It doesn't bother to delve into the disturbing fact that Ben only likes Jemima after she's skinny. Confessions of a Shopaholic and the rest of the series is about shopping addiction and debt, as well as the possible involvement of the financial industry. Slightly more complex, but as everything always works out okay for Becky Bloomwood, you can hardly say this is an intense examination.

Bridget Jones's Diary does deal with a few more issues, including judging by appearances, trying to find self-worth in the midst of a society that tells you you're worth nothing without a husband, the falsity of tabloid journalism and the demerits of weighing under 9 stone. However, Bridget Jones is the best of the bunch, and everything ends with a happy ending that doesn't quite ring true.

Bridget Jones's Diary does deal with a few more issues, including judging by appearances, trying to find self-worth in the midst of a society that tells you you're worth nothing without a husband, the falsity of tabloid journalism and the demerits of weighing under 9 stone. However, Bridget Jones is the best of the bunch, and everything ends with a happy ending that doesn't quite ring true.Valley, with all of its glamour and glitz, never feels false. Despite the blockbuster sensationalism of the subject matter, Susann has a firm grip on what feels real and what a simply realistic ending would be, based on the character's pervious actions and tragic flaws. Pessimistic, possibly -- but then it definitely escapes the dreaded moniker of 'fluff.'

7 comments:

Isn't that funny that to avoid being called "fluff," a book most often doesn't have a happy ending? That sort of defines 20th century literature for me, which I guess is why I read it so sparingly. There are so few 20th century books that are considered "Literature" that have happy endings (I actually can't think of any...) which is often simply dubbed "realism" and not really noted. But is the world really such an unhappy place that books that have unhappy endings are considered more real than those who do not?

I definitely take your point about chick lit being undeniably unreal and fluffy (my forthcoming post on "Super in the City" agrees completely), but it seems to me that there should and can be realism along with happiness not necessarily to the detriment of Literature.

Anyway, good post! I like the comparative nature of it. :)

I hadn't really thought about it, but I suppose you're right -- a happy ending somehow denotes 'fluff.' It might just be that the happy ending is so DONE, so over with, that after over a thousand years of English literature, we're just sick of it and crave something relatively new.

I do think there are more happy endings than you are thinking -- Tolkien, for one, ties everything up nicely, C.S. Lewis has kind of a bizzare pseudo-happy ending to his Narnia series, and there are some more recently that I can't think of off the top of my head. I think the main problem, though, is that with the newer stuff, it's hard to tell what is literature, simply because we don't have the necessary perspective yet.

There's also a growing pessimism in society, though, that probably contributes to the whole real=depressing thing. But good for you for keeping your optimism! I think there is definitely room for both in literature. Maybe we should hunt out some recent books with happy endings that aren't fluff, and give them a separate post?

I love the idea! Recent books that are happy but aren't fluffy! I like the suggestion that happy endings can still survive despite the growing pessimism you mentioned.

I'll have to think on this. What do you have, O English major? :)

I'm thinking on it -- and we have to define 'happy,' definitely. Optimistic? Joyous? For how many characters? Does everyone have to survive? Do the bad guys have to lose definitively?

I'll start a list and narrow it down once we define the happy modern ending :P

I think we should focus on a book being overarching happy. By “happy” here I mean that it has a tone of hopefulness and that the book has ended fairly and properly. This may result in the protagonist’s rightful death, but still have a happy ending, if you follow me. I think the book can still have a happy ending even if there is some death or unhappiness as long as the end is just and exudes a sense of hope for the future. I look at it like the story of Pandora: most of it is really depressing and she does a horrible thing, but that story still has, in my view, a happy ending since even after she unleashes all kinds of evil on the world, there is still hope left at the end.

In other words, “happy” does not necessarily mean a book is all sunshine and rainbows (this would unquestionably be the “fluff” we are avoiding) and it also doesn’t mean that the ending must be a traditional happy ending (girl marries prince under twittering doves and singing chipmunks or something). Although, admittedly, I am a fan of more traditional happy endings where the villain gets his or her just desserts (you know how I love comeuppance) and the protagonist lives happily ever after having done the right thing in terms of offing the villain. They should count on our list, but not be the only definition of “happy” that we’re using.

Does that work for you? Fascinating question, by the way! I love thinking about stuff like this and thus love our conversations!

I found your conversation very interesting and would be interested in what you two come up with. KT I have never read Valley of the Dolls would I like it?

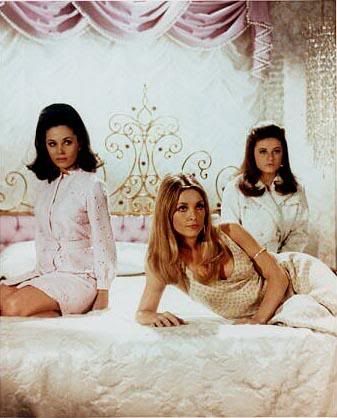

Wey-ull, assuming you're my mother, Anonymous, I think you might like Valley of the Dolls, if you're not offended by prolific drug use. It's in the 1950s, so it's not recreational drug use (i.e., not the 'club scene' or whatever -- it's mostly diet pills and sleeping pills). I enjoyed it -- there was a movie out in 1974, I think, that you probably saw or at least heard about?

Post a Comment